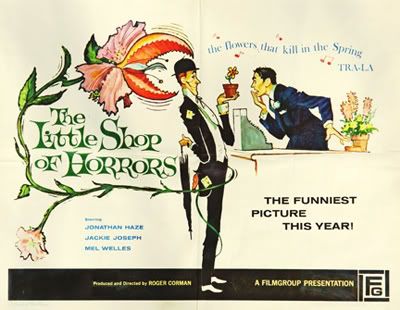

A vintage poster from the author’s collection. Particularly pleasing to me is the mis-quote from Gilbert & Sullivan’s The Mikado, another favorite of mine. It’s almost as if the marketing department were already thinking “musical." Why has no imaginative stage director featured a flower-like, rather than gourd-like, Audrey as seen here?

For about three years I was completely obsessed with the musical. For a strange, shy, closeted, monster-movie loving, Muppet obsessed, over-eating musical theater boy like myself, this was pure catnip. It had everything – great tunes, good jokes, a memorable cast, just the right balance of irony and sincerity, some weird sexual overtones, and the most amazing puppet character ever put to celluloid. I sang the songs, I drew Audrey IIs in class - I even wrangled my way into a puppeteer gig in a 1990 local production (a role I repeated in 2003). Actually my big dream is to play Seymour onstage, but both times I’ve auditioned for the role they thought I’d be better as the cackling, gluttonous monster. This would injure my pride if I didn’t know, deep down, that they are right. Damn typecasting!

For about three years I was completely obsessed with the musical. For a strange, shy, closeted, monster-movie loving, Muppet obsessed, over-eating musical theater boy like myself, this was pure catnip. It had everything – great tunes, good jokes, a memorable cast, just the right balance of irony and sincerity, some weird sexual overtones, and the most amazing puppet character ever put to celluloid. I sang the songs, I drew Audrey IIs in class - I even wrangled my way into a puppeteer gig in a 1990 local production (a role I repeated in 2003). Actually my big dream is to play Seymour onstage, but both times I’ve auditioned for the role they thought I’d be better as the cackling, gluttonous monster. This would injure my pride if I didn’t know, deep down, that they are right. Damn typecasting!

When I realized that the ending of the show had been changed for the film, I was initially unconcerned. After all, I wanted Seymour and Audrey to live happily ever after. But then I heard the cast album…and saw photos of the insane sequence that was filmed and abandoned…and the injustice, the artistic vandalism, the wrongness of it all cut me to the core. But exactly why it’s so wrong is something it’s taken me a while to work out. However, this will be a post (actually several) for another day.

First, let’s just have a look at how this crazy show went from exploitation curio to Off-Broadway hit to big-budget movie, and take note of the major act of vandalism perpetrated when the original ending was changed to a standard Hollywood happy ending.

The original black & white Little Shop of Horrors (1960) achieved notoriety as the quickest of Roger Corman's exploitation quickies. Charles B. Griffith wrote the screenplay, which broadly reprised the plot of his beatnik art-world spoof A Bucket of Blood (1959). The film (originally titled The Passionate People-Eater) was famously shot in two or three days on sets left over from another production, a triumph of Corman’s pennywise ingenuity. With its offbeat humor and memorable man-eating plant, Little Shop became a cult favorite. Because Corman never bothered copyrighting the film, it was often seen on late-night television and was released early and often on VHS.

The plot concerns one Seymour Krelboin (Jonathan Haze), nebbishy minion of the tight-fisted Mr. Mushnik (Mel Welles), proprietor of a dingy skid row flower shop. Seymour is secretly in love with his daffy co-worker, Audrey (Jackie Joseph), and names the strange flytrap he cultivates “Audrey Junior” in her honor. The unusual specimen draws business and publicity to the shop and gets Audrey’s attention, to Seymour’s horror, the odd plant can only thrive on human blood - and demands nutrition with hectoring cries of "Feed me!" Seymour nurtures the plant with his own pricked fingers, and in true demoniac fashion, it flourishes as he withers. Seymour soon grows too anemic to satisfy the growing plant, and so the denizens of skid row begin disappearing. Seymour’s grisly secret is exposed when the plant’s flowers open to reveal the faces of its victims. Guilt and desperation drive Seymour to try to hack up the plant’s insides with a knife, but instead he becomes the plant’s final meal.

When writer Howard Ashman got the idea for a “monster musical” in the late 1970s, he started writing a scenario that unconsciously aped Little Shop. It was only when he caught the film on television that he realized what he was doing and secured the stage rights. Apparently a stage version had already been attempted in France – and if any reader has knowledge of this production, the author would greatly appreciate hearing about it!

Ashman and composer Alan Menken originally went for a very dark tone, with Brecht/Weill sturm und drang dominating the proceedings. Inspired by the early-1960s setting, however, they decided to base the musical’s sound on the pop and Motown of the era, with Phil Spector and the Supremes foremost in their minds. This proved a master-stroke, lightening the tone and providing a score filled with memorable tunes. It also allowed the show to fit neatly into the boom for 50s nostalgia that was so popular in the 1970s and 80s.

Ashman’s script retained only the bare bones of the story, and tightened up the narrative considerably, turning a shambolic spoof into a romantic comedy with Faustian overtones. The action was transplanted from LA to New York, and the cast was reduced to essentials – gone are Seymour’s hypochondriac souse of a mother, the detectives who snoop around after the disappearing bums, and regular customers Mrs. Shiva and Burson Fouch. But the remaining characters were given more depth: Seymour (now Krelborn) was imbued with a romantic yearning that added poignancy to his doomed love affair with the dizzy Audrey, who became tragic sexpot, tangled up in an abusive relationship with the sadistic dentist who figured only tangentially into the original plot. Mr. Mushnik was mostly lost in the translation. Whereas the original Mushnik is the film’s most memorable human character, the show relegates him to supporting status, and replaces his mangled English and broad Jewish humor with a rather more generic irascibility.

The show cleverly transmuted Seymour’s teenybopper groupies into three black street urchins, named Crystal, Ronette and Chiffon, after the famous girl-groups. The girls act as a Greek Chorus, hanging out on the stoop and commenting on the action in tight harmonies. The reduction in cast served the story well – it was economical and intimate. Moreover, in the original film only bit-players and Seymour get eaten, but in the play, only the chorus girls remain alive at the end.

Corman's Audrey Junior was mostly a plot device, immobile and basically helpless, though it did develop the power of hypnotism late in the film. The acclaim it brought the shop seemed mostly due to its genuine novelty. By contrast, Ashman's Audrey II (renamed because few words rhyme with “Junior”) is a scheming smooth-talker who plays on Seymour's insecurities while attracting money and fame through some kind of psychic influence. Audrey II is more mobile and more anthropomorphic, with a trap full of teeth and claw-like branches with which to grab its prey. More importantly, whereas the original plant was a cultivar that looked no further than its next meal, Audrey II was an alien invader with designs on world conquest. The monster was brought to life on stage by Sesame Street alum Martin P. Robinson (he’s the voice and front end of Mr. Snuffleupagus), whose fabulous creations blurred the line between puppet and costume.

Lee Wilkof as Seymour and Marty Robinson as Audrey II in the original New York staging.

Ellen Greene's Audrey meets her namesake in the Off-Broadway production.

Ashman’s script turned Little Shop of Horrors into a tragedy of ends and means. Setting Seymour on the path to his doom, Ashman plays a subtle game with the audience's affections and expectations, making them morally complicit in the killings by offing the most unlikable character first (the dentist), then upping the ante until Audrey herself must be sacrificed. As Ashman stated in 1986, "It was a question of escalating the stakes for him, to make his predicament more and more intense and to make the audience feel more and more ambivalent as to what is going on, and that's how you get pulled into the story." When Audrey is fatally mauled by her namesake, it negates Seymour’s efforts in a classic tragic irony. “You ate the only thing I ever loved!” he cries, before he himself is devoured.

This is more or less where the first film ended, though Audrey does not die in the original. To provide a truly thrilling finale, however, Ashman concocted an homage to exploitation maestro William Castle's The Tingler, in which certain seats were wired with buzzers, and The House on Haunted Hill, which flew a plastic skeleton was flown over the audience’s heads. In Ashman’s low-budget doomsday scenario, Seymour is eaten, and an oblivious entrepreneur starts taking cuttings. Ominous chords play as the three chorus girls slink downstage and narrate how thousands of Audrey II sprouts, sold as novelties, convince their owners to feed them blood and grow until they are able to “eat Cleveland - and Des Moines - and Peoria – and New York - and this theater!" At which point the scrim opens to reveal Audrey II, its branches now giant, grasping claws, with blood-red flowers blooming to expose the undead faces of Seymour, Audrey, Mushnik and the Dentist, trapped like souls in Dante’s frozen hell. As Audrey II uses its branches to crawl towards the front row, hungry mouth agape, the chorus exhorts the audience to resist the siren call of fame and glory. But it is already too late – just before blackout, the plant’s leafy tendrils descend from the rafters to engulf the spectators.

The play opened at the tiny WPA Theatre in Chelsea, where the plant's growth and subsequent takeover could be achieved with great effectiveness. Little Shop of Horrors was a surprise hit and won Best New Musical. Once transplanted to the East Village’s Orpheum Theater, became a long-running attraction. Audrey's tendrils reached around the globe, with simultaneous productions in New York, Los Angeles and London.

In my next post, we'll see what happened when Little Shop made the transition back to celluloid.

REFERENCES:

CINEFANTASTIQUE Magazine

Volume 17, Number 1 (January 1987)

THE LITTLE SHOP OF HORRORS BOOK

by John McCarty and Mark Thomas McGhee

St Martin's Press, 1988

1 comment:

I recently saw the film at a friend's movie night, played with the original ending. Everyone attending has seen the movie before (with the standard, happy ending) except one girl who was totally unfamiliar with it. That girl's reactions were exactly like the original film test audiences -- she loved the movie until Audrey's death, from which point on she loudly complained that the writing was terrible.

Something that maybe was different in the play (?) but was a bit of trouble in the film, is in the movie Seymour never *actually* kills anyone -- the dentist dies of a self-inflicted overdose and Seymour merely feeds his body to the plant. Everyone else, the plant eats on its own without help. Because of this, it was hard to feel that Seymour deserved any comeuppance.

Even if the details were just the same in the staged version, though, it sounds like maybe the interactive 'eaten by the plant' finale would have been enough fun to satisfy the audience. In the movie's original ending, the extended 'watching people be attacked by plants' finale was just kind of upsetting despite the good-quality special effects.

We also watched the bonus features on the DVD, and Frank Oz admitted that the producer had known from the start that the ending wouldn't work on screen.

Post a Comment