When Hollywood beckoned, the creative team faced a huge challenge in preserving the play’s delicate balance of retro satire, heartfelt romance, and black humor. As it happened, the resulting film was entirely charming, with a script that stuck very faithfully to the stage show (the first 20 minutes are almost a line-by-line transliteration of the original libretto) but condensed scenes and dropped songs where necessary and expanded other ideas which could only be suggested on stage. Most importantly, the cast was perfectly chosen and the director, Frank Oz, proved sympathetic to both the humor and the heart of the show.

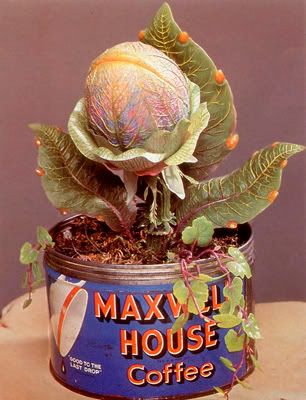

Who could resist this little cutie?

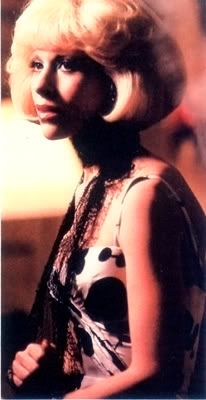

Originally, the film was to be shot on the cheap by Martin Scorsese, in authentic Lower East Side locations. This approach was abandoned for a big-budget production shot entirely on stylized skid row sets, with directorial names such as Steven Speilberg and John Landis mentioned. Despite the ballooning budget, however, Howard Ashman wisely kept his screenplay tight and compact, paring down the narrative to the essentials with not a moment wasted. The production team, determined to preserve the play’s unique appeal, even eschewed the time-honored tradition of ousting the play’s lead actress for a big name. Instead, Ellen Greene reprised her endearing stage performance as Audrey. Lovable schlemiel for hire Rick Moranis was cast as Seymour, veteran character actor Vincent Gardenia became Mr. Mushnik, and Steve Martin turned in a brilliant comedic performance as the dastardly - and none to bright - Orin Scrivello, DDS.

Ellen Greene as Little Shop's battered beauty.

The directorial reigns were handed over to Jim Henson’s long-time collaborator Frank Oz, who performed famous Muppet characters such as Miss Piggy, Cookie Monster and Fozzie Bear. More recently, Oz’s portrayals of Yoda (The Empire Strikes Back, 1980) and Augrah (The Dark Crystal, 1982) had set new standards for believable puppet characters. Geffen felt Oz, though a neophyte director, had the comic touch, emotional sensitivity, and puppetry knowledge to make Little Shop work on screen. Oz quickly proved the producer correct. Though helming a lavish multimillion-dollar production, he steadfastly refused to "open up" the play, eschewing both MTV-style flash and conventional staginess. To preserve the play’s emotional intimacy, and to keep the disparate plot elements from devolving into the absurd, he favored a subtle, economical approach that let the material speak for itself. Instead of complicated choreography, he paid close attention to the rhythms of natural movements, and keyed them to the musical beats. To emphasize the characters’ cramped, claustrophobic existences, Oz kept mostly to medium shots and close-ups rather than panoramic cityscapes or intricate camera movements. Robert Paynter’s lush faux-Technicolor cinematography savored the rich colors and weathered textures of Roy Walker’s ingenious sets. By sticking to the essentials, Oz achieved a level of conviction and believability rare for a movie musical, creating a self-contained world where everything, from a spontaneous ballad to an unexpected total eclipse, felt oddly natural.

Crucial to the film’s success was the blues-singing Audrey II. In keeping with Oz’s desire for immediacy and realism, no stop-motion or composite shots were used. Instead, special effects wizard Lyle Conway created a series of incredibly complex hand- and cable-controlled puppets, requiring anywhere from three to fifty operators. The detailed designs and effective puppetry, combined with the jiving, conniving baritone of Levi Stubbs (of the classic soul group The Four Tops), made Audrey II a delightfully unique screen villain instead of just another special effect.

Frank Oz (right) with Lyle Conway and Audrey II.

The biggest challenge of all was to translate the play’s famous proscenium-busting ending to celluloid. Various approaches were considered, including making the entire film a dream, or turning Seymour into a crazed figure shouting, "You’re next!" a la Invasion of the Body Snatchers. In the end, Oz decided to go for broke with a spoof on Godzilla-style monster mayhem that saw Manhattan under attack by giant plants and a foreboding “The End!?!” caption.

However, the faithful translation of the stage show to film was not to be. At the test screening held in Orange County, California, the family-demographic audience was quite positive about the film, laughing in all the right places and even applauding the musical numbers. They especially enjoyed Steve Martin's flamboyant turn as the pompadoured Orin Scrivello, DDS. But the mirth stopped cold once Audrey and Seymour died, and titanic plants took over the world.

Giant plants cackle merrily as New York burns.

According to Oz, no audience response cards were needed to know that the ending wasn’t appreciated. "When Seymour and Audrey died the audience was totally silent. They were waiting for something to happen and when it didn't, they were very angry at us." Oddly enough, the apocalyptic finale was one of the factors in making the stage show such an unexpected success. Oz credits this adverse reaction to the differences between stage and screen verisimilitude. "On the stage you know it's a felt puppet. You know they're going to come back for a curtain call...With film it's very powerful, and you really believe they're dead." The emotional truthfulness Oz had strived to capture worked against him: "If I had turned around and made it very funny and campy, then the problem of their deaths would be like saying 'Hey, it's OK, don't take it seriously.' Then I would have betrayed the people that really cared for the characters."

David Geffen, who backed the off-Broadway show, and whose company also produced the film, had predicted that the downbeat ending would not be accepted, though he boldly allowed filming to proceed. However spectacular, the $5 million sequence was now relegated to the cutting room floor, and another ending was needed – fast. In the new ending, Audrey recovers from the plant attack, and Seymour takes advantage of the flower shop’s demolition to electrocute the plant with an exposed power line. The two lovers then flit off to Audrey's suburban fantasy-land…where an Audrey II seedling lurks, smirking, in the flowerbeds.

"Oh, shit!"

It is a tribute to everyone involved that this new ending does not entirely dissatisfy. Indeed, the characters as impersonated by Rick Moranis and Ellen Greene are so appealing that one wants them to survive, and the "surprise" appearance of another plant (a venerable monster-movie ploy) somewhat alleviates the taste of sugar-coating - not to mention opening up the way for a sequel. Nevertheless, devotees of the stage show stringently objected to the change. "If I hadn't shot the original ending then I might have agreed that I should have," the director exclaims, "But I shot the goddamn thing! I tried it! But the audience is a very dynamic part of a movie. You don't make a movie for yourself, you make it for the audience."

But which audience? That is where Warner Brothers made their crucial mistake - they intended Little Shop to be a family-friendly holiday movie, when in fact, it was a weird cult item (albeit one that cost $30m to make). Forcing it into the feel-good mold warped the film out of shape.

In the following posts, I will argue that the whole conception of who Little Shop of Horrors was for was off. This came from the marketing department, not the artists, and led to the decision to change the ending and fatally damage the story. By providing Little Shop with a Hollywood happy ending, Warner Brothers not only abandoned one of the greatest FX sequences of all time, they turned a funny, charming but essentially serious and moralistic parable into a delightful but spiritually hollow movie. My ultimate hope is that Warner Brothers will do us the favor of releasing a deluxe “director’s cut” DVD and let the movie be seen as it was intended.

Next - how changing the ending changed the proverbial moral of the story.

REFERENCES:

CINEFANTASTIQUE Magazine

Volume 17, Number 1 (January 1987)

Volume 17, Number 5 (September 1987)

CINEFEX Magazine

Number 30 - May 1987

FANGORIA Magazine

Number 60, January 1987

LITTLE SHOP OF HORRORS (Photo Novel)

by Robert and Louise Egan

Perigee Books, 1986

THE LITTLE SHOP OF HORRORS BOOK

by John McCarty and Mark Thomas McGhee

St Martin's Press, 1988

3 comments:

Ellen Greene's final scene is wrenchingly beautiful and when Rick Moranis reaches for her hand as she is swallowed... so good. Properly edited, they should re-release this film with it's intended ending. I'm surprised they didn't when the revival came about.

I can cut that giant plant on pieces and eat it :-)

I love this film, but the original ending is pathetic B grade horror film. Perhaps they could have used some shots as a flash into the future when proposing to sell clippings though.

Post a Comment