Read more after the jump...

In 1969, composer Andrew Lloyd Webber and lyricist Tim Rice embarked on an ambitious project to dramatize the last days of Jesus Christ, from the night before Palm Sunday through to the Crucifixion on Good Friday. The duo had already had a success with Joseph and the Amazing Technicolor Dreamcoat (1968), based on the Biblical story of the "coat of many colors.” But where Joseph was a light-hearted affair aimed at younger audiences, the new project would take a much more serious and ambitious tone. Tim Rice remembered being fascinated with Judas, whom he felt got something of a raw deal from history. After all, without Judas' betrayal, the sacrifice of Christ could never have happened. Did not Judas, then, play a crucial and thankless part in the salvation of humanity? With this compelling central character in mind, Rice and Lloyd-Webber began work.

Unable to find a theatrical producer for the resulting show, and inspired by the success of The Who's double album rock opera Tommy (1969), the songwriting duo struck a deal with MCA to release the story as a concept album. Jesus Christ Superstar (1970) was a hit, and was followed by productions on Broadway and the West End before being filmed by Norman Jewison in 1973.

Tim Rice’s script leaves the supernatural aspects of the story off-screen and puts the focus on the politics of ancient Judea, as seen through the lens of pop culture celebrity. Rice's Judas is a disillusioned activist who views Jesus as a spiritual leader who has begun to believe his own hype. Judas feels that Jesus’ formerly humble ministry has become a cult with an anti-authoritarian message that threatens both Jewish religious leaders and their Roman occupiers. Judas’ conviction that he must stop Jesus before the authorities crack down on the Israelites leads him to betray his friend, but once Jesus has been betrayed, Judas realizes that the ancient prophecies have been fulfilled after all.

An opera of the Passion would be daring enough even without this sympathetic portrayal of Judas – no opera composer in the 300 years from Monteverdi to Puccini had dared put Christ on the stage. But Lloyd-Webber and Rice, inspired by the success of Tommy and Hair (1968), set the story to a propulsive rock beat, and shone the light of modern pop culture on the tale. The alchemical word “superstar” (a brand-new term coined by Andy Warhol) challenges us to ask whether divinity itself is just another form of celebrity (or is celebrity a debased form of divinity?) and whether religions are just glorified fan-clubs. Judas warns Jesus in "Heaven on Their Minds" that his followers will turn when he fails to deliver on every promise - and we are reminded of the gleeful way tabloids rip into stars who disappoint us with their fallible humanity. Jesus gains immortality by dying young - and we are reminded of James Dean and Marilyn Monroe. It's heady, provocative stuff, wrapped up in an irresistable package of witty lyrics and memorable tunes.

This take on the story owes a lot to Tommy, whose titular idiot savant becomes an unwitting celebrity-cum-messiah in a pop cultural hall of mirrors before being torn down by his followers. Both stories are laced with satirical humor, but Jesus Christ Superstar improves on its model by including a heartfelt sense of tragedy and emotion. Though Tommy rocks harder, JCS feels deeper, and rather than undermine the traditional tale, the ironic sensibility makes the story feel fresh, startling and relevant. The Superstar album also featured a full cast, whereas in Tommy all the parts were sung by the four members of The Who. Jesus Christ Superstar came along just as the "Jesus Freak" movement was gaining steam, as some hippies started to realize they did not need to turn their backs on religion, and that Christ's message of universal love and forgiveness was, like, right on, man. The long hair and muslin duds don't hurt, either. Though "Jesus Freak" came to be used as a catch-all pejorative for the obnoxious Bible-thumpers, it should be remembered that the origin of the term is self-deprecatingly good-humored. Though JCS's harder edges do not quite fit the movement's "Summer of Love" afterglow (the British are always skeptical of unalloyed happiness) it wins points with the image of Jesus as the ultimate counterculture outsider, a spiritual radical whose vision of universal brotherhood places him at odds with the forces of worldly power.

Jesus Christ Superstar came along just as the "Jesus Freak" movement was gaining steam, as some hippies started to realize they did not need to turn their backs on religion, and that Christ's message of universal love and forgiveness was, like, right on, man. The long hair and muslin duds don't hurt, either. Though "Jesus Freak" came to be used as a catch-all pejorative for the obnoxious Bible-thumpers, it should be remembered that the origin of the term is self-deprecatingly good-humored. Though JCS's harder edges do not quite fit the movement's "Summer of Love" afterglow (the British are always skeptical of unalloyed happiness) it wins points with the image of Jesus as the ultimate counterculture outsider, a spiritual radical whose vision of universal brotherhood places him at odds with the forces of worldly power.

On the radio, 1969 heard Norman Greenbaum's "Spirit in the Sky" and the excellent rocker "Jesus is Just Alright", performed by The Byrds on the Easy Rider soundtrack and later a big hit for the Doobie Brothers. Jesus Freaks invaded Broadway in May, 1971 (months ahead of JCS's October debut), with Stephen Schwartz's Godspell. A much more earnest take on the material, with tunes by the songwriter of the current hit Wicked, Godspell is a perennial favorite of amateur and church theatre troupes. The two shows leap-frogged each other from stage to screen, with both films coming out in 1973. Unfortunately the urban-Christian-hippie vibe of the Godspell movie has dated rather badly in contrast to the JCS film's more surreal vibe. The score included a chart hit with the lovely ballad "Day By Day."

The original UK album cover.

THE MUSIC

Musically, Jesus Christ Superstar is a mélange of styles, leaning heavily on riff-based Brit rock (such as Deep Purple and The Moody Blues) but with Broadway-style chorales, some vaguely Middle-Eastern sounding flourishes, even a smattering of vaudeville. ("Herod's Song" began life as a 1967 Eurovision entry called "Try It And See".)

The "tribal rock" vibe owes a debt to Hair (the tribe here being the Israelites instead of the Flower Children) and songs like “What's the Buzz?” and “Simon Zealotes" wear this debt on their sleeves. Likewise, “I Don’t Know How to Love Him” stands side-by-side with “Easy To Be Hard” as the two best pop-rock theatrical ballads of the period.

Lloyd-Webber here pioneers two techniques, one which he has used throughout his career and the second which he eventually dropped. The first and most notable is the repetition of musical themes set to different, contrasting lyrics, such as in “The Temple.” Unlike the classic Wagnerian motifs, his themes don’t develop to show character or plot progression, relying instead on the lyrics to lend the repetitions irony and depth. His approach is more akin to the obsessive re-working of themes as exemplified by his idol, Beethoven (thanks to the fabulous Amy Douglas for this insight!)

The second – no doubt abetted by the freedom of the recording studio – is the abrupt transition, without segue, between musical sections of different time signatures and keys. Note the use of this technique on “What’s the Buzz? / Strange Thing Mystifying” and “Damned for All Time / Blood Money” to signify characters butting in on somebody else’s songs. Lloyd-Webber would later phase out this style of songwriting, but he used it to very dramatic effect in Evita (1978). The transitions are very tricky to achieve live and are often softened on stage.

Interestingly, the music lends Jesus Christ Superstar the sense of fate and mysticism missing from the libretto. Whereas Tim Rice’s book focuses exclusively on the political aspects of the story, Lloyd-Webber laces his score with ominous and ecstatic touches which hint at a larger spiritual meaning. In particular, the spooky, modernistic themes of the Overture, the Crucifixion and “John 19: 41” evoke awe, terror and pity, as well as the hushed, tense aura of the Tenebrae. These passages are seemingly inspired by the work of Hungarian composer György Ligeti, which became famous when used in 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) to represent the aliens’ mind-expanding influence on humanity. Whereas Ligeti’s music in the Kubrick film accompanied Bowman’s transformation into a higher being, in Jesus Christ Superstar a similar theme accompanies the Passion sequence to suggest that what is occurring is not just an execution, but an apotheosis.

CONTROVERSEY AND CHARACTERIZATION

The “Christ as celebrity” angle is audacious, and the decision to tell the story through the eyes of a sympathetic Judas guaranteed the project a degree of controversy. Also controversial was the choice to portray the story in strictly secular terms. Though the religious aspect to the story is never explicitly denied by the text, it is never confirmed either, leaving the viewers to make what they will. The story ends with the Crucifixion, leaving the Resurrection off-stage and ambiguous (many productions interpolate a Resurrection during curtain calls, a move of dubious artistic value). What is a little unclear is that Judas was presumably present for the walking on water, the healings, and other miracles, so why does he now disbelieve in Christ’s divinity? Or was he home sick those days? Also, Judas apparently visits Earth after his suicide to sing the title song – so he has an afterlife, but Jesus’ postmortem fate is left ambiguous? Or is Jesus imagining Judas' final say? It’s a bit muddled.

Some critics have leveled charges of anti-Semitism against the work, for its frankly villainous portrayals of Caiaphas and Annas. However, I find this unconvincing. The Pharisees here are simply “The Man” out to crush anything that threatens their power, and their Jewishness, per se, comes into it not at all. It’s all too easy for the machinations of the Pharisees and the Romans to blur into a Sunday School recitation of motiveless perfidy, but Tim Rice’s script does an excellent job of elucidating the conflicting loyalties and spheres of influence at work in this Imperial colony.

Judas has always been a cipher in Christian theology – he has no book of his own, his role among the Disciples is vague and reports of his death are contradictory. His motivations for betraying Jesus are left blank, being portrayed in the Gospels merely as the fulfillment of prophecy. This raises a number of theological questions about the role of free will in a universe of prophecy and fate, all of them too complicated to get into here. But needless to say, the character of Judas is a rich and fertile field for speculation, and provided Tim Rice and Andrew Lloyd-Webber a lead character full of conflict and ambiguity.

In Tim Rice’s script, Judas is disillusioned with Jesus and his movement, which he feels has become a cult of personality. He is jealous of his formerly privileged position at Jesus' side ("I've been your right-hand man all along") and resents the other Disciples and their rowdy coterie of camp followers and hangers-on. Moreover, he is disturbed by Jesus’ claim that he is Son of God and King of the Jews, and fears reprisals from the Jewish religious authorities or the Roman army. He regards himself as the only person with any sense left in Jesus’ band of followers and the only one willing to challenge Jesus rather than be a star-struck yes-man. Only after his betrayal, with Jesus headed for execution, does he realize what he’s done, and begins to see himself not as the last sane man but as an unwitting pawn in God’s design.

Judas is a reformer, not a revolutionary, and views Jesus' movement as a ministry of social work rather than something transcendent or epoch-making. Perhaps Judas' stance may be likened to the Liberation Theology in vogue in the 1960s. He believes in good works and social justice, though he has no desire to upset the social order. Jesus’ followers have too much “Heaven on Their Minds” to pay attention to the realities of life under Roman rule. “Listen, Jesus, don’t you care for your race? / Can’t you see we must keep in our place? / We are occupied / Have you forgotten how put down we are?” he cries.

It is not much of a leap to think that different disciples would have had their own expectations of Jesus' movement - as we know, the interpretive conflict between Peter, Luke and Paul have shaped the church to this day. But Judas' stubborn pragmatism reveals his low horizons - he is focused on the practical, rather than spiritual, aspects of Jesus' movement. He decries Mary Magdalene for washing Jesus’ hair in expensive oils, since the money spent on the oil could have gone to the poor. Undeniably true, but he misses not only the symbolism of the act but the value of simple, kind gestures. He works for Mankind, but he is no humanist at heart. Similarly, he scorns the Magdalene’s association with Jesus on the grounds that it looks bad for them, never realizing that it is Jesus’ open and non-judgmental heart is the key to his greatness.

The character of Jesus is rendered with a fine sense of a man who feels himself called by destiny, and while we feel for his trials, he is kept at an arm’s length, remote and mysterious. This Jesus thinks of himself as divine – and since the miracles of the Bible are not portrayed, we are left to wonder – but frightened by the hard road ahead and burdened by his follower’s expectations. This Jesus has a sharp tongue that he uses on his Disciples in “What’s the Buzz” and “The Last Supper,” and a temper unleashed in “The Temple.” His inner journey through fear and doubt and towards an acceptance of his fate is given full expression in the gorgeous aria “Gethsemane.” It’s a nuanced and sensitive portrayal of the most difficult person in human history to depict in fiction.

The show humanizes Pontius Pilate without letting him off the hook. Introduced with the haunting “Pilate’s Dream” song, Jesus Christ Superstar portrays the infamous governor as smug and arrogant, but reluctant to execute an innocent man just to satisfy the crowd. He is bemused both by Jesus’ passivity and the mob’s bloodthirstiness, and while he tries to be reasonable, it finally becomes easier to nail a man up than deal with civil unrest. Life is cheap in the Roman Empire, after all, so one less Galilean is small price to mollify the querulous Jews.

Mary Magdalene is given little characterization other than “the whore with the heart of gold,” but she does get to sing the excellent “I Don’t Know How to Love Him,” which was a hit for Yvonne Elliman. Other than the scene where Peter denies Christ, the rest of the Disciples are given no depth and scant lines, acting more as a chorus than a collection of characters. However, the Disciples get one of the funniest lines in the show, during “The Last Supper” as they muse that “when we retire we can write the Gospels / So they still will talk about us when we’ve died.”

THE FILM

Barry Dennen, who played Pilate on the album, on Broadway and in the film, deserves credit for getting the Jesus Christ Superstar movie produced. While appearing in Norman Jewison’s 1971 film of Fiddler on the Roof, Dennen suggested that Jewison make Jesus Christ Superstar his next project, and lo, it came to pass. Thanks, Barry!

Jewison wrote his screenplay with British television and film auteur Melvyn Bragg. Faced with the problem of finding a way to meld the contemporary sound and attitude with the ancient and venerated subject matter, they hit upon the idea (inspired by, or at least cross-pollinated with, the Godspell film's putting its flower-power disciples into the gritty urban setting of New York) of a motley crew of vaguely hippie-ish actors performing the show in the Israeli desert. So, Jewison and the cast schlepped out to the Holy Land and filmed entirely on location among Biblical-era ruins, including an amphitheatre and King Herod's palace.

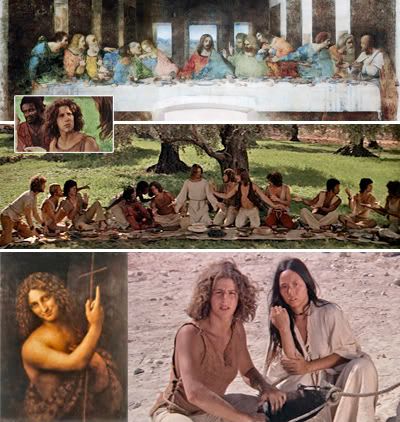

This brilliant move heightened the theatricality of the film while giving cinematographer Douglas Slocombe (whose later credits included all three Raiders of the Lost Ark films) the opportunity for epic vistas and striking tableaux. The diverse elements gave everything a surreal aura and avoided the absurdity of singers gyrating amidst too-realistic sets and costumes. The ruins are evocative and abstract, while lending a powerful sense of authenticity. The desert, mountains and valleys are gorgeously epic in wide-screen, with tiny figures framed against the awesome landscapes. The one bit of green in the parched landscape is the verdant olive grove of Gethsemene (not the actual location, though it does still exist). The flower-power styling of the cast brings a riot of color and movement to the bleached, monochrome desert.

A dilapidated colonnade provides a venue for "Simon Zealotes."

Another impressive ruin doubled as Pilate's house.

Much use was made of the scaffolding on archeological sites, which echoed the set design of the Broadway production. Black-robed Pharisees perch like giant crows.

By allowing the present day to mingle with the past, Jewison acknowledges the dolorous history of a region torn apart by tribal and religions differences. Roman soldiers pack machine guns as well as spears, arms dealers and dope-peddlers inhabit the Temple, and Judas' agonized debate over his betrayal is interrupted by the sudden appearance of a line of Israeli army tanks.

Jewison follows the album's tradition of keeping mum whether Jesus is divine, or just a charismatic leader. But, cleverly lending some ambiguity, Jesus is not among those leaving the bus in the opening sequence - he just appears among them - nor is he seen boarding the bus with the cast at the end. However, the cross is seen to be empty, and as a sunset shimmers behind it, a shepherd leads a flock of sheep across the bottom of the screen (on the DVD commentary, Norman Jewison insists that this was an unplanned bit of serendipity). Another powerful moment comes "Gethsemene," when he sees his fate flash before his eyes in millenia of religious icons.

The film soundtrack was orchestrated and produced by André Previn, the pianist, conductor and composer. Previn was principal conductor of the London Symphony Orchestra at the time of the filming, and he conducted that famous group for the film soundtrack. Previn’s long, Oscar and Grammy studded career encompassed classical, jazz, Broadway and film scores. His version of the Superstar score is lush, with some of the harder edges sanded down, but it still packs a punch. Previn’s jazz piano improvisation in the Crucifixion scene is an apt counterpoint to the choral soundscape.

ORIGINAL ALBUM VERSUS FILM

In general, I prefer the original concept album and cast to the film soundtrack. The sound is straight-up rock with orchestral touches and closely-miked vocals. It features faster tempi and more guitar than the film sound track, and Lloyd-Webber's sudden transitions are in full force. Since it was made as an album and not a cast recording, some of the songs, such as “Heaven on Their Minds” and “Everything’s All Right” are allowed to groove into long fade-outs, making them more satisfying listening experiences.

Yvonne Elliman and Barry Dennen reprise their roles of Mary Magdalen and Pontius Pilate from the original album, and in both cases give excellent performances. Elliman, of course, went on to sing the disco classic "If I Can't Have You" from Saturday Night Fever, and cult movie fans might be interested to know that Dennen provided the voice for the wheedling, treacherous Skeksis Chamberlain in The Dark Crystal.

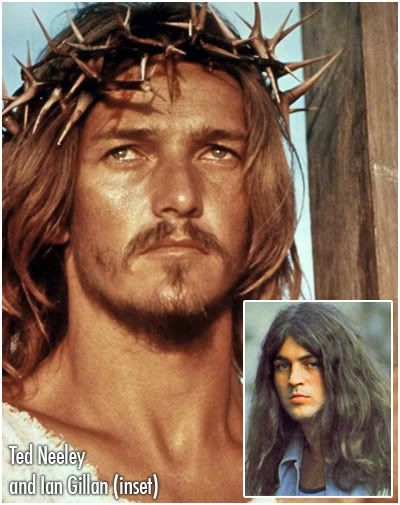

Jesus Christ Superstar fans are hotly divided on their Jesus of choice. Both Gillan and Neeley follow in the footsteps of Robert Plant the with high-octane tenor wails that will become the standard heavy metal vocal style throughout 70s and 80s. On the original album, Ian Gillan (of hard-rock pioneers Deep Purple) imbues Jesus with an aggressive, earthy quality and impressively growly high notes. He never played Jesus onstage, so his acting chops are a mystery. He was asked to appear in the film, but his touring commitments with Deep Purple prevented this.

Ted Neeley understudied Jesus on Broadway and was the original Claude in Hair. He gives an excellent, impassioned performance as Jesus in the film, and certainly looks the part, with his wide-set eyes giving him a mystic, faraway gaze. Neeley's voice takes on an irksome tremulous quality in some quieter passages, but his yowling high notes are spine-tingling, especially in “Gethsemene.” He toured for years with Jesus Christ Superstar, and was a featured vocalist in Meat Loaf's early 80s concerts.

Opinions are just as divided about which Judas is better, with the original Murray Head competing with Broadway's Ben Vereen and the movie's Carl Anderson, whom most people consider definitive. I am going to come down as a firm partisan of Murray Head's performance on the original album. Head’s sandpaper tenor registers both cynicism and yearning. It’s the voice made for delivering barbed comments, but there is an underlying sense of wounded emotion that always bleeds through. He makes “Heaven On Their Minds” a cry from the heart, and his sardonic “Strange Thing Mystifying” assures us that while he doesn’t object to the Magdalene’s profession - surely he's availed himself of similar professionals - he certainly objects to her place in Jesus’ esteem. He gives a powerful rendition of “Blood Money” and in “Pilate’s Death” he yelps like a hunted animal, his voice cracking on the “I Don’t Know How to Love Him” reprise and drowning in torment as he cries to God, “You have murdered me!”

Murray Head is best known today for speak-singing the 1984 hit “One Night in Bangkok,” from the musical Chess (lyrics by Tim Rice, music by Björn Ulvaeus and Benny Andersson of ABBA) but has also had success as a recording artist in the UK, France and Canada. His two major film roles were in The Family Way with Haley Mills (1966) and Sunday, Bloody Sunday (1971). A still of Head from The Family Way is the cover of The Smith’s Stop Me best-of album. Murray Head is the older brother of Anthony Stewart Head, well-known to cult audiences for his roles in Buffy the Vampire Slayer and Doctor Who.

Carl Anderson took over the role of Judas from Ben Vereen on Broadway, and went on to play the role in Los Angeles. The power and charisma of his Judas is undeniable, and while I prefer Murray Head, Anderson’s performance is unimpeachable. It must also be said that he nails the funky rave-up “Superstar,” putting the album cut to shame - and I doubt Murray could have pulled off the white fringe! As fabulous as this number is, it's the only point where the film goes over-the-top into realms of questionable taste. Has Judas died and gone to Las Vegas?

Anderson got two Golden Globe nominations for his appearance in the film, and went on to a long career in film, television and recordings. He also played Iscariot in numerous touring productions. Sadly, he died of leukemia in 2004, at just 59.

Here's Carl performing "Superstar" on The Tonight Show, apparently in the late 1990s. Still sounding amazing after all that time, and with even better diction!

While the casting of a black man as Judas seems tailor-made for controversy, everyone involved has denied this was ever a consideration. Having an African American playing one of the most (unfairly?) reviled characters in history does seem like a deliberate provocation - especially when he ends up swinging on a noose like so much strange fruit, but Anderson's performance transcends easy political point-scoring. For better or worse, it is now traditional that an African American plays Judas in stage shows – Corey Glover, lead singer from In Living Colour, recently toured with Ted Neeley.

Josh Mostel gives a hilarious performance as Herod in the movie, but he can’t compare with Manfred Mann singer Mike d’Abo’s vocals on the record. The only real mis-step in the film cast is the use of Kurt Yahgjian as Annas – his breathy falsetto might have been intended to sound unearthly, but instead he sounds comical. Annas was Caiaphas’ father-in-law, but is instead portrayed as a strangely effete junior priest. Odd.

Larry Marshall gives a wild-eyed performance as Simon Zealotes, though musically I enjoy the "megaphone" effect on John Gustafson's album performance, and it gives the idea of appearing before a giant crowd instead of dancing frenetically right up in Jesus' face! However, both Marshall and the dance routine are great, and the lyrics are easier to understand in the film. It's a well-directed sequence as well, with a swirling blur of dancers amid ruined columns. Judas looks on in disgust at the hysteria, Romans watch from the sidelines as Simon incites Jesus to revolt, and Jesus himself stands still and calm at the center of a swirl of passion.

The Disciple John is played by Richard Orbach, a strikingly pretty young dancer with long curly hair. This is a clever bit of casting, as John, the youngest Disciple, is traditionally been portrayed as a long-haired boy. In Leonardo's "The Last Supper," he sits at Jesus' right hand, and is so androgynous that he is often thought to be Mary Magdalene. Orbach looks strikingly like Leonardo's John the Baptist, with the same hair - different John, but the same idea. Witty, well-informed casting for a non-speaking role which might easily have gotten lost in the crowd.

THE LEGACY

Along with Hair, Jesus Christ Superstar is now recognized as one the seminal rock musicals, groundbreaking shows that proved it was possible to integrate a modern rock sound with the narrative demands of the theatre. The film, in retrospect, looks like a long-form music video that integrates rock performance, stage conventions and cinematic vision into an exhilarating whole. The original album still sells well, and the stage show is constantly being revived and sent out on tour, attracting ardent fans and prompting debate about the true nature of faith and fame in ancient Judea and today.

Rice and Lloyd-Webber would strike gold once more with the even more successful Evita (concept album in 1976, original London production in 1978), which explored similar themes of politics and the cult of personality. Che stepped into Judas' shoes to undermine the adoration heaped upon the lead character. The partnership of Rice and Lloyd-Webber broke up with some acrimony soon after, but the three shows they created together stand as some of the most enduringly popular works of modern theater.

NEWS FLASH - Rice is currently penning lyrics for Lloyd-Webber's sequel to The Phantom of the Opera (1986), which will see the Phantom escape to 19th Century Coney Island. Er, what? Time will tell what becomes of this project.

* * *

Last but not least, here's the rarely-seen promotional clip for "Superstar" as performed by Murray Head. It's an oddly static clip with terrible lip-synching, but interesting for its place in the history of the show.

2 comments:

"It’s the voice made for delivering barbed comments, but there is an underlying sense of wounded emotion that always bleeds through."

That's an excellent summation of Head's vocal qualities...I've been listening a lot to Chess as of late and he's perfect on those barbs in "Bangkok" and "The American and Florence", but that wounded emotion you note is entirely what defines his "Pity the Child".

Truth be told, I've not listened to the original album very much- I have it on LP but have always preferred the film version (it's my favorite film of all time). I really need to give it a listen sometime soon...

There is only one voice for Jesus and that's Ian Gillan. It's a shame he wasn't available for the film. It would have been far more successful. Needly is awful. As for Judas, I recently heard a fantastic version of the musical with Josh Young as Judas. He is now my favourite. Now if we could get a Gillan look-a-like/sound-a-like and Young to perform in a film version for a remake, it would be amazing.

Post a Comment